Professor Robin McInnes, a geologist, coastal scientist and art historian, explains how watercolours provide important insights into the state of the coast before photography.

The idea of using historical works of art to support coastal management came to me during a visit to Tate Britain in 2007. I was examining the painting by William Dyce of Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th 1858 from the point of view of a geologist and coastal scientist. It occurred to me that the detailed portrayal of the chalk cliff geology, the wave cut platform on the foreshore, the beach and the coastal defence structures could form a reliable record of coastal conditions at this location on that exact date. This raised the question as to how many paintings, watercolours and prints existed for other coastal locations, and were they true representations of the coastline?

Since then, I’ve been studying historical art for clues to understanding the rate and scale of change affecting the British coast. Coastal paintings, drawings and prints show us how things were in the past and inform us about future changes that may result from climate change and rising sea levels. They describe the physical impacts of cliff erosion, landsliding or inundation, as well as environmental change and the progression of coastal development particularly through the Victorian and Edwardian periods. Works of art extending back to the late 18th century, long before the days of photography, may provide the only record of our changing coast over time.

Art can, therefore, form a useful benchmark when assessing the nature, scale and rate of coastal landscape evolution. I have found watercolours to be the most valuable medium on account of its fine detail and accuracy. One particularly useful point of comparison has been between the watercolours painted by William Daniell from 1814-1825 (which were published as a series of aquatints called Voyage Round Great Britain) and equivalent views captured by the contemporary watercolourist David Addey between 1995 and 2002.

My latest report, The State of the British Coast: observable changes through imagery 1770–present day, is to be published in April 2019. Here are just a few of my findings.

Whitby, North Yorkshire

The port of Whitby, overlooked by St. Hilda’s Abbey on the headland, forms one of the most painted locations on the north-east coast. Although the more resilient coastal headlands experience very slow rates of coastal erosion, the coastal frontages in the vicinity of Whitby have been affected by significant change, including major landsliding events.

William Daniell RA travelled down the Yorkshire coast painting Whitby and Scarborough in 1822. He was working on his Voyage Round Great Britain series (1814-1825) comprising 308 colour aquatint engravings of British coastal scenery. This view looks south towards the harbour mouth with the unstable cliffline in the foreground.

Beginning in 1995, the watercolour artist David Addey retraced William Daniell’s steps to produce an updated set of views. This watercolour from Daniell’s vantage point shows a defended and stabilised coastal slope. Major works at a number of sites were undertaken along the North Yorkshire coast following coastal instability events in the 1990s. You can see how the headland has been eroded as well as the urban development on the headland between the artist’s viewpoint and the Abbey.

This photograph, taken in 2009, gives a sense of the changes that have taken place over the years, and also the accuracy of the two artists’ portrayals of the scene.

Holy Island, Northumbria

The dramatic scenery of Holy Island in the north-east of England has enticed artists for centuries. Bearing in mind the undeveloped nature of this coastline, and the effective management arrangements for its Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, together with protection of nationally and internationally important geology and habitats, there appears to be remarkably little observable coastal change over the last two centuries. Lindisfarne Castle, other fortifications and buildings of religious importance in the area have been repaired or maintained over time. Future changes in terms of coastal erosion and sea flooding are largely dependent upon the impacts of climate change.

Castle on Holy Island Northumberland, 1822, William Daniell

Image © Trustees of the British Museum

This view, taken close to High Water, shows Lindisfarne Castle in good condition structurally and compares with the view by John Wykeham painted in watercolour 30 years later.

Holy Island Castle, Lindisfarne in the Distance, August 1855, John Wykeham Archer

Image © Northumberland Estates

This very detailed watercolour by John Wykeham Archer (1855) shows the view looking west (inland) with Lindisfarne Priory beyond.

David Addey painted this view from the beach in 2002 at Low Water. The castle has lost its battlements and some of its walls and the slope at the beach appears to have eroded.

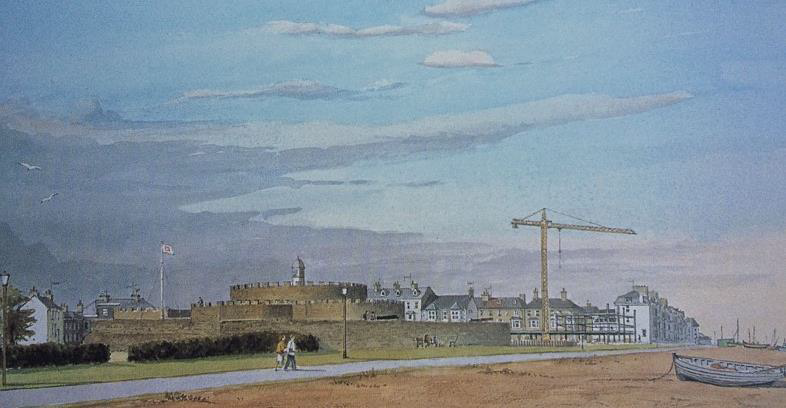

Deal Castle

At the time of William Daniell’s visit in 1823, Deal Castle in Kent belonged to the government but was of lesser importance because of the establishment of peace with France. The castle was depicted in detail by Daniell, who was a very accomplished architectural draughtsman, and he clearly shows the proximity of the structure to the steeply sloping beach.

When you compare Daniell’s image with the watercolour produced by David Addey in 1988, it can be seen that a significant portion of the original castle buildings have been removed, including the Tudor rose layout of the fortifications that had been constructed during the reign of King Henry VIII in 1540. Further damage was incurred when the castle suffered a direct hit in the Second World War. The castle is now protected by a substantial beach, and the coastline has been defended with a concrete sea wall approximately 20m seaward of the foremost element of the castle defences.

Professor Robin McInnes OBE is a geologist, coastal scientist and art historian. His consultancy Coastal and Geotechnical Services is based on the isle of Wight.