In 1699, when she was in her early 50s, the naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian left her home in Amsterdam and set sail for Suriname in search of insects. The 7,500km voyage would take around two months to complete, and she stayed for almost two years. The detailed pictures she made of the animals and plants that she found there were ground-breaking, changing people’s understanding of the country’s wildlife and cementing Merian’s reputation as one of the most important naturalists of her era.

Merian was set on the path to Suriname from an early age. She was born in Frankfurt in 1647, the daughter of Johanna Sibylla Heyne and printmaker Matthäus Merian. Her father died when she was young, and in 1651 her mother remarried the artist Jacob Marrel, known for his depictions of plants and flowers. Marrel taught Merian to draw and paint, and instilled in her a passion for botanical art that was central to her own career.

Four Tulips: Boter man (Butter Man), Joncker (Nobleman), Grote geplumaceerde (The Great Plumed One), and Voorwint (With the Wind), c.1635-1645, Jacob Marrel

Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Licence: CC0 1.0

As a child Merian was fascinated by insects, particularly butterflies, moths and silkworms, and would “collect all the caterpillars I could find in order to see how they changed”. Metamorphosis was only partially understood at the time. For centuries, people had assumed that butterflies were born out of dead caterpillars, but scientists such as Jan Swammerdam (1637–1680), who studied insects under the newly-invented microscope, were beginning to challenge that idea. Merian read the latest research with interest, and was soon illustrating her own findings. She published her first study, The Wonderful Transformation of Caterpillars and their Particular Plant Nourishment, in 1679.

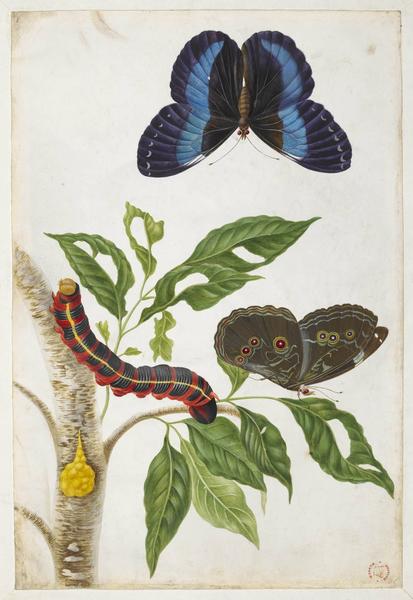

Untitled (from ‘Erucarum Ortus, Alimentum et Paradoxa Metamorphosis’), 1718, Maria Sibylla Merian

Image © Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth. Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees, All Rights Reserved

Merian’s illustrations were exceptional for their time, detailed and scientifically accurate (she was careful to draw the insects at life size) but with an element of artistic flair. Rather than paint them diagrammatically, Merian depicted her specimens in motion, crawling and flying around the plants that sustained them. It was an innovative approach that must have captured people’s imaginations. Her career flourished as she moved around northern Europe, first with her husband, the artist Johann Andreas Graff, and later with her two children Johanna Helena and Dorothea Maria after her marriage broke down.

Untitled (Panorama of Amsterdam from the river Y), 1702, Ludolf Backhuysen I

© Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

In 1690, Merian settled with her daughters in Amsterdam. The port city was a busy global centre of art, research, trade and commerce, and she found much there to inspire her. Merian befriended experts such as Jan Commelin, who worked at the botanical gardens, and visited the collections of merchants and scientists who had amassed plant and animal specimens from around the world. But her enduring interest in metamorphosis left her wanting more. She could only learn so much by studying dead caterpillars, butterflies and chrysalises; she needed to see them in the flesh. “All this stimulated me to take a long and costly journey in order to pursue my investigations further.”

Untitled (Pineapple), c.1701-1705, Maria Sibylla Merian

© Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Merian found the specimens from Suriname, on the northern coast of South America, particularly fascinating, and presumably learned more about the place from her son-in-law Jakob Hendrik Herolt, who traded there. The country had been confirmed as a Dutch colony in 1667, and towards the end of the century Merian managed to secure permission to travel there on a five-year independent research trip – an unprecedented achievement for a woman at the time. She sold off hundreds of her paintings to fund the voyage, and set off with her daughter Dorothea Maria on 10 July, 1699.

Untitled (Two examples of a blue butterfly), c.1701-1705, Maria Sibylla Merian

© Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

On their arrival the pair took a house in the capital Paramaribo and set about collecting, studying, and recording the abundant new plant and animal species that they found in the country. Their research was broad; Merian painted exotic fruits such as bananas and pineapples (which she found particularly delicious), and a host of unusual creatures including iguanas and frogs as well as her beloved insects. She noted down how they were referred to and used by the indigenous communities in Suriname, and recorded her frustration at the lack of interest many of her Western acquaintances showed in the local flora and fauna: “they mocked me for seeking anything other than sugar.” In 1701 Merian was forced to cut her trip short due to illness, but she had already travelled extensively within the country and found species that nobody had studied before.

Metamorphosis of a Frog and Blue Flower, c.1700-1702, Maria Sibylla Merian

© Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Back in Amsterdam she found an enthusiastic audience for her research. After “several nature-lovers had seen my drawings,” she recalled, “they pressured me eagerly to have them printed. They were of the opinion that this was the first and most unusual work ever painted in America.” Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, an exquisitely illustrated study of the insect life of Suriname, was published in 1705, after which she embarked on an expanded and updated compendium of her European studies, Erucarem Ortus. She never saw the final publication, which was completed in 1718, a year after her death.

In the 300 years since then, Merian’s work has been celebrated and relied upon by generations of scientists and naturalists. Carl Linnaeus made early use of it when he systematically classified plant and animal life around the world. He even named several species, including two butterflies, in her honour. Her Surinamese studies offered European people an early and spectacular glimpse of South American flora and fauna, and her illustrations set a new standard for naturalist illustration. Merian’s fascination with metamorphosis transformed her own life and changed a scientific discipline in the process.